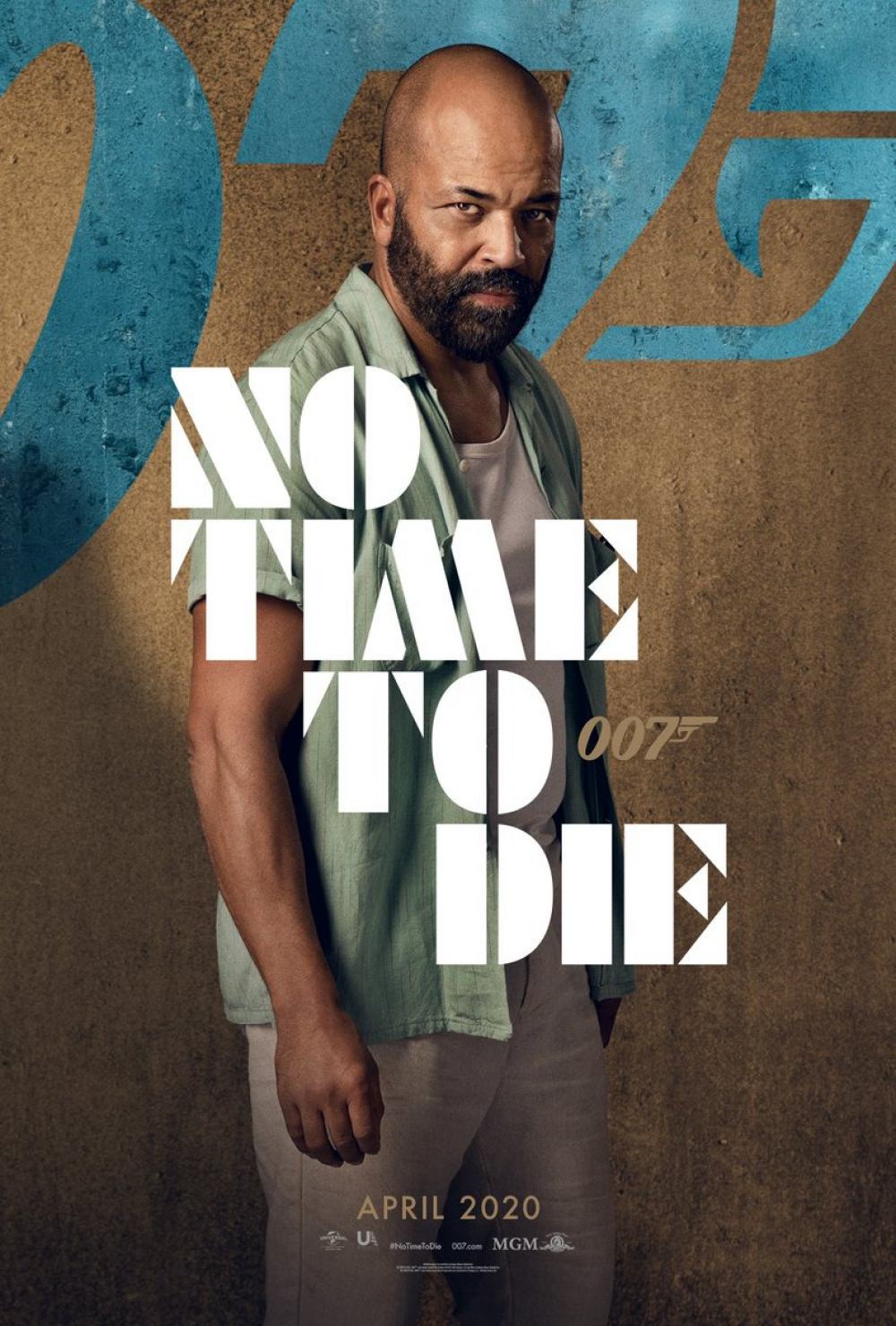

Photograph: Dan Jaq/Nicola Dove/Allstar/MGM/Universalīut the Americans, in the form of his old buddy Felix Leiter (Jeffrey Wright) and an uptight new state department appointee Logan Ash (Billy Magnussen) persuade Bond to take on the job as a freelance, and send him to Cuba, where he liaises with an untrained operative: Paloma – a witty and unworldly turn from Ana de Armas whose rapport with Craig recalls their chemistry in Knives Out. ‘Another in the endless gallery of antagonists who have conceived a personal obsession with Bond himself’ … Rami Malek. But a shocking act of violence destroys their idyll, as we knew it must, and Bond has some spectacular stunts as he hurls himself from a bridge.

#No time to due movie#

Photograph: Dan Jaq/Nicola Dove/Allstar/MGM/UniversalĪnd Craig’s final film as the diva of British intelligence is an epic barnstormer, with the script from Neal Purvis, Robert Wade and Phoebe Waller-Bridge delivering pathos, drama, camp comedy (Bond will call M “darling” in moments of tetchiness), heartbreak, macabre horror, and outrageously silly old-fashioned action in a movie which calls to mind the world of Dr No on his island.ĭirector Cary Fukunaga delivers it with terrific panache, and the film also shows us a romantic Bond, a uxorious Bond, a Bond who is unafraid of showing his feelings, like the old softie he’s turned out to be.Ī queasy and dreamlike prelude hints at a terrible formative trauma in the childhood of Dr Madeleine Swann (a gorgeously reserved Léa Seydoux), that enigmatic figure we saw in the last movie who is now enjoying a romantic getaway with James. Department stores even sold kits for taking the drugs, which were marketed as a nice present for those fighting on the frontline.Lashana Lynch and Lea Seydoux in No Time to Die.

Nazi soldiers took the drugs to increase their alertness and vigilance, according to the outlet.Īlso during World War II, Russia's Ministry of Defense gave every Russian soldier on the frontline a 100-gram ration of vodka called the commissar's ration, according to a report from Macalester College.Īnd in World War 1, according to the BBC, cocaine and heroin use was common among soldiers. While there's no evidence that fighters from the Wagner Group are taking drugs, there is a long history of drug-taking in conflict.ĭuring World War II, Nazi Germany administered amphetamines, which were touted as a "miracle product," according to TIME.

"It looks like it's very, very likely that they are getting some drugs before attack," the soldier told CNN. "You shoot them and more come constantly," one soldier said, according to AFP.Īnother Ukrainian soldier told CNN in February that advancing Russian forces looked like a "zombie movie" as they climbed over "the corpses of their friends." Ukrainians earlier speculated that Russian soldiers were taking drugs in November as winter began to make the fighting ever more miserable, telling AFP that Russian soldiers seemed like "zombies." Otherwise, how can they go to certain death, stepping over the rotting corpses of their colleagues? You can go mad a bit." "Our guys are wondering if they are on drugs. "They are killed and they come again," he told The Times. The unit's media officer told The New York Times that 10 to 15 Wagner fighters were advancing on their position, to their almost certain deaths, every day during the first month of fighting. It's the kind of behavior that soldiers from Ukraine's Third Assault Brigade, which is now fighting the Wagner Group in the key eastern city of Bakhmut, believe could be the result of taking drugs. Fighters from the Wagner group are notorious for storming frontline positions and enduring severe casualties.Ī retired US Marine estimated that the average life expectancy of a Wagner soldier on the frontlines in eastern Ukraine is just four hours. And a 48-year-old prison inmate who exchanged his freedom to serve in Russia's Wagner Group told the Wall Street Journal earlier this month that the group only trained him for three weeks and that he expected to die on his first mission. The group once sparked controversy when it offered convicted Russian prisoners freedom in return for fighting. The Wagner Group is a powerful Russian paramilitary unit that has emerged as a key ally in Russia's advance inside Ukraine.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)